Monday, April 14, 2008

English agriculture and the basis for English hegemony.

Somehow life got better without the little minds of government being intimately involved.

by StFerdIII

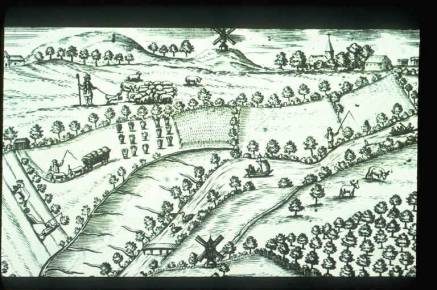

A fascinating historical fact – which even Ivy trained superiors who love to talk down to working stiff inferiors might care to read about – is the untold story of English agriculture and its magnificient explosion of innovation from 1650 to 1750. Without this shift from subsistence to munificience in agricultural output, England never would have hd the population, the tax base, the military resources, nor the mass of entrepreneurial and scientific talent to dominate the world. It is a story rarely told.

An economy cannot jump from feudalism to industrialisation. Agriculture and stable food supply, is the first and most important sector and factor, which needs mondernisation before a sustainable industrial base can be created. The lessons from the English experiment are appropriate for today.

England became a world power for many obvious and sundry reasons. It was an island which could sit out the interminable and bloody intra-European wars which savaged other states. It was a naturally situated maritime state. Under Henry the VIII and his daughter Elizabeth, the English navy was built and England turned to the sea for safety and foreign influence. English shipping and economy grew rich off of pirateering and Spanish plunder; ships became better, faster and more manoeuverable than its competitors.

Its system of government and its checks and balances were innovative – especially during and after the Cromwellian civil war and the not so 'Glorious' Revolution of 1688, feeding the economic surplus which was gathering from 1650 and onwards into an ever increasing spiral of naval power. In short Marx's capital 'rent' was suffusing a system which was constitutionally and contractually far ahead of any competitor.

But what truly allowed English sea, naval, and eventually trade and military dominance was the creation of advanced agricultural practices and thereby, a massive increase in manpower and population. This increase in numbers fed the growing naval power of England; whilst increasing the local economy, its tax base and its economic dynamism – rooted in private property ownership, profit making and contractual law. It was the impulse of agriculture in a system of governance unique in Europe, which gave England its first and lasting advantage in the competition between nation states.

This unique combination of factors gave the English the basis upon which to dominate trade routes; sezie key points to protect those trading interests; and enforce those national interests with naval and military power. By 1750 no competitor could possibly catch England until the rise of America, and the creation of a united Germany. For by this time the English were supreme in agriculture.

English agricultural techniques by the mid 18th century were simply the best in the world. The most advanced ideas were implemented tying the land, via improved and superior transport routes to the London and thereby European market. By 1750 thanks to advanced land usage, transportation density, and a large local population protected by water from foreign invasion, the English had created a truly integrated and vibrant national economy.

English law was a major catalyst in the explosion of food stuffs – varied and plenty. The major benefits of farming went to individuals who owned their own land, invested in machinery and technology, and were creative in getting needed product to the growing market centers of the country. As more food was made available the population grew. As the population grew there arose more demand for food stuffs and thereby, a greater propensity for profit.

English agriculture thus became a commodity- much like any other capitalist good. Land and farms had real value and the more productive and innovative and economical the plot of land, the more money it was worth. By 1800 the 'European' peasant, so typical from France to Siberia had vanished from England. In 1750 after the 'Enclosure acts' were passed which guaranteed private property rights and the ability to enclose and expand farmable land, the profit motive, tied to a growing urban market became paramount. This in turn allowed innovation to flourish.

The English farmers – both large and small – made remarkable progress between 1750 and 1850. Livestock appearance changed. Gone were scraggly, thin and ugly sheep and cows. Created and bred were the short stocky and square looking sheep we see today – looking fat and contented. Cows increased dramatically in size and usefulness. Draining, irrigation, hedging, crop rotation and new grains rapidly appeared. Machinery was employed on a vast scale by the mid 18th century, leading to a cycle of experimentation, improvement and productivity increases.

In fact English agricultural productivity skyrocketed from 1750 to 1850. Typically a feudal or peasant based agricultural system would produce at most a 1% increase per annum, in productivity. In England productive rates of output were 4-10 times this level. No other state could keep up. By the early 19th century steam power was common on English fields, as farms became larger and economies of scale improved further improving profits and supply. Concommintly the English population exploded going from 8 million souls in 1798 to 22 million by 1850 – nearly a tripling in 2 generations.

It was this increase in food, productivity, profits and manpower which fueled English expansion overseas. England exported people to populate the Anglo-sphere around the globe. The Royal Navy become larger and had more sailors than the 5 next largest navies combined. English machinery, production skills and ingenuity became legend and quite profitable. In essence the resolution of food and food supply generated English hegemony.

And the lesson today? Limited government based on contractual law, private property and the market mechanism works. There were no government subsidies in 1750 England, for 'new agro practices' such as we have with ethanol or corn today. Government did not pick winning and losing farmers, landlords or technologies. They did not subsidise an earth friendly plough, a eco-regulated horse harness, or a clean air steam engine. And thanks to that food production blossomed and lives were saved.

But there is a similarity with the stupidity we see today in government and in government's keen desire to distort the agricultural market. Since the English parliament was controlled by landed interests, they of course over time, excluded foreign agro-produce and limited imported trade. How similar this is today with 'eco-laws' and 'fair labor standards' being applied to imported product from poorer nations. This protectionism contributed directly to the famines which swept Ireland in the 1830s and 1840s. But by this sorry chapter in history, the English domestic agricultural revolution had already succeeded and it spawned in essence, everything else.

Yet the lessons remain. The more government distorts a market the more disastrous the effects. In extreme cases it leads to death – witness today the government protected rice market of the Phillippines now going through a famine. In other cases taxpayer money is wasted and spent on dumb ideas from paying farmers not to grow produce, to forcing planters to switch to corn to partake of huge corn subsidies. The result of course is an increase in food prices, and higher consumer costs.

The English became world hegemons because they eschewed during a critical period, and then reversed after a laspe, insidious government interventionism in agriculture. It is a lesson well worth remembering.