Monday, September 11, 2023

From Aristotle to the Big Bang and its metaphysical gospel.

The Pantheistic, Materialistic nature of Science and $cientism.

by StFerdIII

“The human mind, no matter how highly trained, cannot grasp the universe. We are in the position of a little child, entering a huge library whose walls are covered to the ceiling with books in many different tongues.” Einstein

Atheism asserts that there is a latent conflict between religion and ‘science’. Ironically this theorem has little historical support and ignores the epistemological data to the contrary. Epistemology is the study of knowledge and within this domain broadly speaking, there is a paucity of inclusive treatments within the realities of both the scientific and the religious experience and their often intertwined if not inter-dependent dimensions. In short, they are not mutually exclusive and when a layman analyses and critiques the ‘scientific truths’ of the day, he will often remark that what is offered seems rather religious.

The ‘Big Bang’ theorem is religiously held by its adherents as proof of material dialecticism and endless time. The most rabid proponents are Atheists, though many religious also believe in and support the doctrine. The Bangers hang their hats on ‘science’ which they rarely define beyond referencing a ‘scientific method’, an explanatory framework of scientific discovery that has many different interpretations and implementations. However, the Bang theology in many forms, has a very long history.

Pantheism, Aristotle and the Greeks

Aristotle’s work ‘On the Heavens and Meteorologica’ (4th century BC) is a pantheistic view deifying nature and assigning various Gods which had been invented in most ancient cultures, including the Greek, to explain the marvellous creation and design of life and the Earth and related natural phenomena. Socrates had previously taught that all matter, whether animate or inanimate contained a ‘soul’ which forced the object to ‘achieve is purpose’. In Aristotle’s work, the deification of nature used this concept to develop the ‘Prime Mover’ idea, or divine source which directs the physics of motions and planetary states.

In this model all activity is naturally induced to reach a ‘natural place’, both sublunary and superlunary (below and beyond the moon). Aristotle’s universe is pantheistic, not geometrical or mathematical and it differs in significant ways from the Christian and medieval view.

Pantheism is naturalism or ‘the universe’. It is the theological belief that nature and the universe reflect Gods (plural not singular) and nature in general. These deities or forces are the controllers of the mysteries found in natural phenomena, physics, states, matter and energy. Humans are just a part of this naturalist-pantheist creation and no anthropomorphic principle or concern is at work. Pantheism offers no theological insights into humans or the creation of sentient creatures. The Big Bang theory is very similar in this regard.

For Aristotle and his pantheistic eternity, the Prime Mover created the Universe, but it was not created ‘out of nothing’ as the Bangers believe. Motion and physics were assessed but no mathematics was deployed to explain motion. Gods of many gaps were built to sustain the planetary and universal frameworks of motion, energy and life.

From Pantheism to Maths

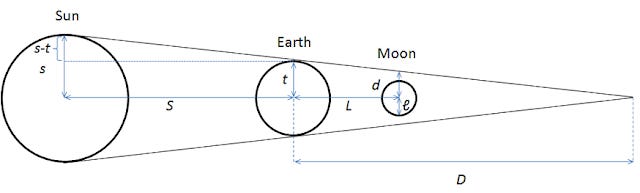

Opposed to Aristotle’s view were other Greeks who were moving from pantheism into hard maths. Pythagoras’ academy in the 5th century BC, which predates Aristotle’s by 100 years, and in the person of Philolaus, formed ideas of earthly sphericity and motions of the planets around the centre of the Cosmos and its ‘central fire’. Such a model was later opposed by Aristotleians. Eratosthenes (275 – 194 BC) moving away from pantheism, used a geometrical model to calculate the size of the spherical Earth. Aristarchus (215 – 145 BC), greatly amending the Pythogorean concept, used a similar geometrical framework to deduce the dimensions of the earth-moon-sun system and proposed heliocentricity as a workable model of what was observed in space from earth, detaching planetary motions from pantheistic controls.

Ptolemy and back to Pantheism

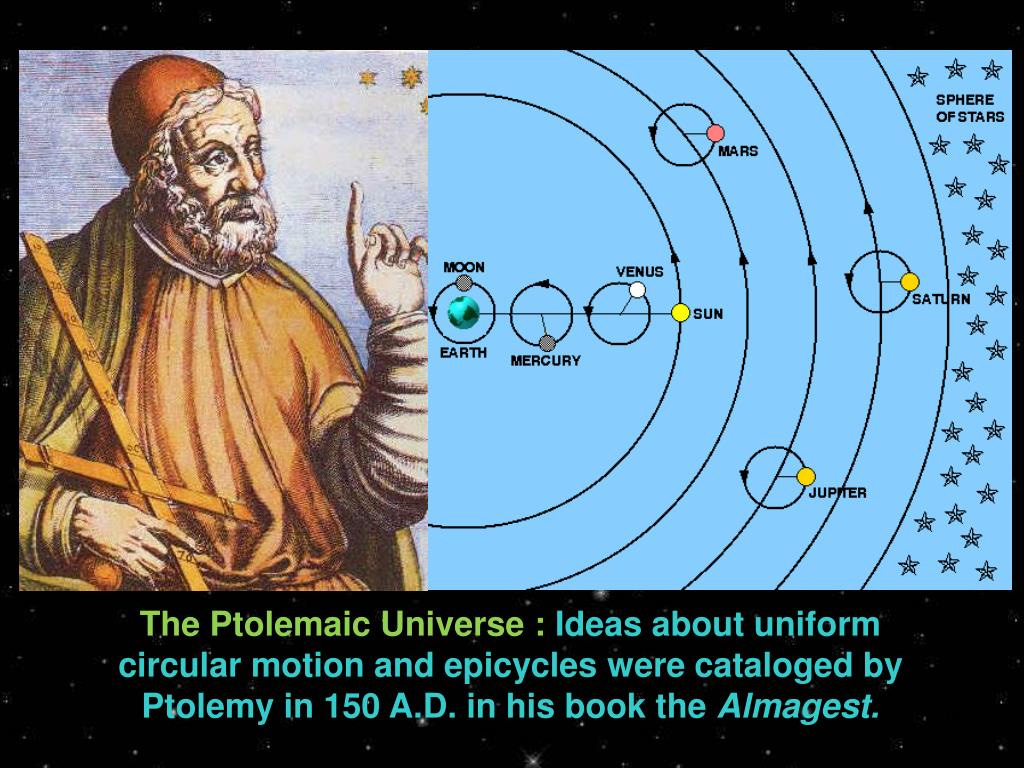

Ptolemaic science (2nd century AD) was built on the above and outlined planetary motions, orbits and time within a structured solar system. However, in this model the earth was stationary and the planets revolved around it, thus upending Aristarchus’ heliocentric model and deploying Aristotleian pantheism to explain structure and motion. Ptolemy’s model was thus regressive and at odds with the maths of Aristarchus. Within the Ptolemaic universe, Aristotle’s animism is also apparent with the coordination of planets described in terms of humans.

The anthropomorphic principle is clearly apparent in Ptolemy’s models, with the earth at the centre of creation, a supporting plank for monotheists and the nascent, growing Catholic Church (2nd century AD). The problem with ancient Greek science and with Ptolemy’s model, was the theological-pantheistic barrier to understanding motion.

A comprehension of motion was only achieved by Christian theism and its scientists as they sought to uncover the ‘Prime Mover’ and how and why objects actually move and why planets keep their orbits. In this search for the ‘5 proofs’ of God’s existence, these men ran into much violent opposition for about 1000 years. Ptolemy’s model was staunchly defended by many in power, especially in the universities and secular-funded observatories.

The reigning paradigm always creates a caste of people who benefit and have power they are loathe to lose. The Catholic Copernicus who rediscovered heliocentricity in the early 16th century, was trained and funded by the Church. Famously it was not the Church or Rome he was worried about when he displaced the earth from the centre of the solar system. His concerns in publishing his theory centred on the violent opposition given by the academics and universities.

Christian Theism and the Universe

St Paul the evangelist, argued for a well-reasoned faith and worship (Romans 12:1). Athanasius the great Catholic theologian (296-373 AD) defended the logos of Christ (which can be seen in the plasma theory of universal matter) and the rationality and logical reasoning of ordered creation. Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430 AD) picked up this theme to lay down the principle that if conclusions of science about the natural world contradicted scripture, then scripture had to be reinterpreted. John Philoponus (570 AD) was the first astronomer to argue that since stars shine with a different colour they were composed of ordinary matter (pagans and the ancients gave stars godlike attributes eg Mars, Venus, Jupiter).

As tooling and knowledge improved so too did mathematics and physics. Centuries of observations and calculations led to Jean Buridan (1295-1358 AD). Buridan was propelled by a study of Aristotle’s pantheistic eternity and theorised that God the Prime Mover imparted a certain quantity of motion to celestial bodies to keep them in orbit in a purposefully created frictionless void, or inertial motion (the mover and objects are now separated). Oresme (1320-1382 AD) who succeeded Buridan at the Sorbonne, viewed the universe as clock-work using inertial motion, an idea which would inform Cartesian linear inertia and Newton’s mechanical laws of motion.

Copernicus (1473-1543 AD) used the ideas of Buridan and Oresme to improve on the doctrine of ‘impetus’ and the earth’s motion in space. Johannes Kepler (1571-1630 AD) provided the complicated trigonometry to help prove Copernican theory. Newton, Leibniz and popularisers of science such as Voltaire, reoriented science to articulated and provable mathematics fully disengaging medieval science from the Greek pantheistic theories. Heliocentricity, gravity, laws of motion and calculus were produced (see Stanley Jaki, The Road to Science and ways to God, 1978).

The great breakthroughs were in understanding motion and optics (Roger Bacon and others late 13th c). In any event thanks to Christian deism scientific theory had to be provable, replicable, observable and mathematically supported. It was a ‘quantum’ leap in science. More here