Friday, November 3, 2023

$cientism and Louis Pasteur as a case study. Part II

Theories and fraud in lieu of real science and proof – Germs, Viruses, Stabbinations

by StFerdIII

In Part I about Louis Pasteur, it was offered that much of his work was of great scientific value and merit. A long list of real scientific discoveries is certainly attributable to Pasteur and his associates, many of them beneficial, verifiable, and reproducible. However, when the trained chemist strays into diseases, immunology and poisoned concoctions named after the cow, he is supremely out of his depth, reflected in the fraud, misuse of data, and even outright mendacity in forwarding claims around the germ theory of disease, flying viruses which spread infections and stabbinations which provide succour and safety for the afflicted.

In short, Pasteur made the unfortunate but predictable journey from scientist to Scientism. Like the unimpressive venal corrupt quack Edward Jenner, Pasteur became a Public Relations salesman, a sophist and hand-waver, eager to accrue credit, assets and attract the adoring gaze of a redeemed, sacralised, and saved public. The rush to fame if not fortune prevented the Catholic Pasteur from entering the narrow gate.

Hume’s criticism

We now turn our attention to a very dense and excitable book on this aspect of Pasteur by Ethel D Hume ‘Béchamp or Pasteur’ first published in 1923. The investigator is very hostile to Pasteur and his ‘science’, and this should be borne in mind. Transparently she does declare this bias, which is unlike ‘modern science’ which hides their worldviews and sources of finance and the power cliques which direct their ‘research’. No need for transparency in ‘modern science’.

This book ravages all of Pasteur's work and discoveries which seems rather excessive. In essence, fermentation, silkworm infection, viniculture spoilation, biogenic life creation and other claimed discoveries by Pasteur are alleged frauds, with Pasteur stealing the ideas, conclusions, and even experimental proofs from Béchamp and others. It is more likely that many researchers were involved in the same domains, doing different varieties of experimentation, and given that most were writing letters and sharing information it is rather intolerable that we ascribe fraud to all of Pasteur’s work. It is better to discern the good from the bad. So, we will skip much of the book and focus on the 3 main areas of controversy, germs, viruses, stabbinations and the related fraud and deceit. Hume’s detail is meticulous and much of it has been confirmed by observations and research since 1923.

Hume and Antoine Béchamp

Hume adores Béchamp and sets him up as the protagonist against the ‘Machiavellian’ if not demonic Pasteur. A summary of Béchamp’s life and accomplishments renders the man as great a scientist as Pasteur, perhaps greater. Yet he is not remembered, was never feted, nor even applauded. He spent his entire career in the shadow of Pasteur dying some 13 years after Pasteur, but never receiving due approbation. Béchamp declared throughout his career that Pasteur purloined many of his ideas and conclusions from his own research. Disagreements between the two men included the following as found in Hume’s book.

1. In 1858 Béchamp was the first to prove that moulds accompanying fermentation contained living organisms and could not be spontaneously generated. He recorded his experiments in his 1858 memoir, six years before Pasteur came to the same conclusions publicly, declaring that spontaneous generation was impossible. Pasteur did acknowledge that Béchamp’s work was ‘meticulous’ and correct and had preceded his but gave no indication if Béchamp’s experiments directly affected his own or were copied in some way. Béchamp never received recognition that he had in fact disproven spontaneous generation before Pasteur (a central tenet still held by Darwinists, many atheists and ‘scientists’).

2. Pasteur offered his germ theory of disease during the early 1860s, stating that each kind of ‘pathogen’ or germ which he described as airborne ‘animals’ or microorganisms, produces one specific ‘fermentation’ or disease-like effect. Béchamp however proved that a microorganism might vary its fermentation based on the surrounding medium or environment. Béchamp’s experiments showed that these ‘microforms’ as he called them, under varying conditions, might even change their shape. These observations were reproduced by Felix Loehnis and N.R. Smith of the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1916.

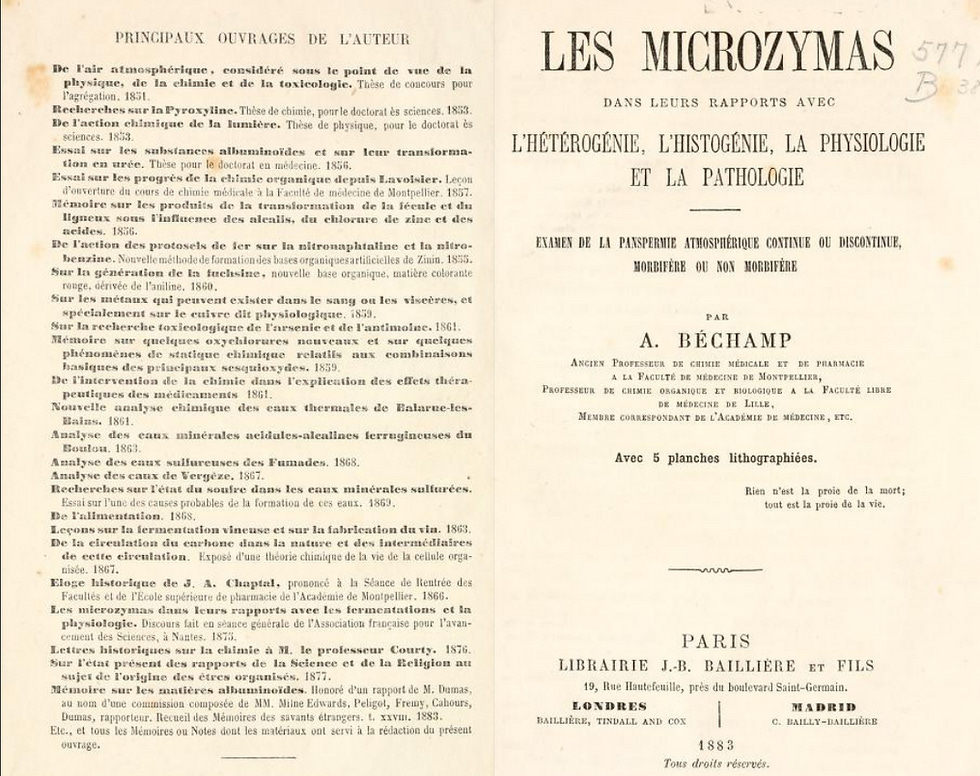

3. By 1866, after very thorough experimentation, Béchamp had discovered that chalk rock which is common in the Paris basin, seemed to be formed mostly of mineral or fossil remains of a ‘microscopic world’ containing organisms of infinitesimal size, which he named ‘microzymas’ and which he believed were or had been alive. In 1866, he sent the Academy of Science a memoir called On the Role of Chalk in Butyric and Lactic Fermentations, and the Living Organisms Contained in it. After more geological examinations, he wrote a paper in 1870 entitled, On Geological Microzymas of Various Origins. He was convinced that these microorganisms were alive, and possessed life cycles and complexity that were not understood.

4. Béchamp’s discovery of microzymas refuted Pasteur’s germ theory. He referred to microzymas as the builders and destroyers of cells. It is the destructive aspect, or the “end of all organization,” which causes disease, not perambulating, flying germs or viruses. In his very meticulous and professional manner, Béchamp always found microzymas remaining after the complete decomposition of a dead organism and concluded that they are the only non-transitory biological elements. In addition, they seem to carry out the vital function of decomposition (or they are the precursors of bacteria, yeasts and fungi which decompose a dead body). These ideas are opposed to those of Pasteur who blamed diseases on exogenous factors, namely poisoned ‘germs’ and ‘viruses’ who ‘transmitted’ their poison through the air or through touch.

5. Microzymas became the foundation for Béchamp’s principle of pleomorphism, which was in direct conflict with the monomorphic theory of Pasteur. Today the monomorphic view is the only accepted paradigm of disease generation, premised on the theory that through a binary fission, most bacteria divide transversely (crosswise), to produce two new cells which eventually achieve the same size and morphology as the original. Pleomorphists accept the transverse division of bacteria but maintain that bacteria demonstrate complex life cycles including filterable and pathogenic (see Felix Lohnis, 1922, entitled Studies upon the Life Cycle of Bacteria).

6. For Béchamp and pleomorphists, disease occurs when the ‘terrain’ or internal environment of the body becomes favourable to pathogenic organisms. Human disease occurs as a malfunction of physiology due to changes which take place when metabolic processes (such as pH levels), are out of balance. Pathogens which have complex life cycles (a fact confirmed from the 1960s onwards) will take the opportunity to stimulate symptoms within a human body when an imbalance erupts, and if uncorrected, a disease. In this view, the human body is a ‘mini-eco system’ to quote Béchamp, and not a sterile static state as evinced by Pasteur.

7. For Béchamp, microbes or microzymas naturally exist in the body (a fact since confirmed, we have billions of them), and it is the disease that reflects the deteriorated condition of the host and changes the function of these microbes or microzymas. The terrain of the body, once distorted and affected, generates disease endogenously meaning that exogenous factors in disease generation such as ‘germs’ or ‘viruses’, cannot be accountable nor valid.

8. Based on the above, if the pleomorphist-microzymas theory is true, all stabbinations of chemical cocktails into the blood stream will do nothing except weaken the terrain of the body further, adding more misery and dislocation to the host, along with disease and incapacity (a proven fact with mRNA injections which have led to SADS, cancer, blood disease and many other ailments).

This is the essence of Hume’s work when you strip out the rather tedious references to endless fraud and plagiarism. Many researchers work on the same problem at the same time. Not all of them are stealing and plundering from each other. But fraud most certainly did exist, and Pasteur undoubtedly lied, disseminated, made up data and ignored contrary evidence (all of this is provided by Hume in much detail). More here